Translation as a cross-cultural information exchange and exchange activity has the nature of dissemination. Combining communication and translation helps make translation an open, dynamic, and comprehensive discipline. Translators play the role of gatekeepers in communication studies. The choice of a translator is affected by any change in the translator himself, such as his personal preference, motivation, life experience, aesthetic orientation, psychological factors and values, which can call for different translations to be produced. The translation of classics is not like the translation of ordinary works. It puts forward higher requirements for the translator. The beauty and subtlety of its words and characters require the translator to have a profound knowledge of the target language; its connotation and thought are broad and profound, and the translator needs to understand the source language. Transparency of this understanding. And such a master is really rare, and it is difficult to cultivate, so excellent translation works of classics are not common. In addition, translations are becoming more and more diverse, and there is inevitably a mix of people and irregularities in the intermediate translations. This paper explores the translation of classics that combines machine learning technology with the perspective of communication, and proposes an efficient translation model. The experimental results show that the model can effectively improve translation efficiency and accuracy.

Communication studies recognize translation as a cross-cultural activity of information exchange and transmission, inherently possessing the characteristics of communication. Both communication and translation share a common feature: the process of converting and transmitting information [4]. The definition of translation in communication studies offers a new perspective, moving beyond the traditional linguistic-focused research to more open, interdisciplinary exploration. Traditionally, translation has been regarded as the conversion of linguistic symbols, emphasizing the certainty of language and equating the quality of translation with fidelity to the original text. In this view, equivalence has been considered the core of translation, with a focus on faithfulness to the original [2,3].

In contrast, newer research perspectives expand the understanding of translation beyond mere cross-lingual conversion. These approaches account for subjective factors, such as the translator’s role and the audience’s diverse needs. In the 1980s, the translation studies school emphasized the importance of the translator as an active subject [15]. As both a reader and interpreter of the original text, the translator is seen as capable of modifying the text and imbuing it with new meaning, highlighting the translator’s agency. Integrating concepts from communication studies into translation, scholars have introduced elements such as subjects, information, audience, media, and effects into the field, synthesizing various factors within translation activities [8,6].

Translation, as an interdisciplinary field, intersects with history, anthropology, psychology, and linguistics, among other domains. The process of translation involves numerous elements, including the translator, the content conveyed, the audience, and the communication effects. The 5W communication model proposed by the American communication scholar in 1948—”Who? What? To whom? Through what channel? What effect?”—provides a framework for understanding translation dynamics [13]. These elements form a dynamic system, where changes in any one factor can lead to corresponding changes in others, resulting in different translations of the same work [14].

The definition of Chinese classics remains open to interpretation, with varying understandings among scholars. According to the “Ci Hai” dictionary, classics refer to “various important documents of the nation, also known as various books and classics.” Chinese classics serve as carriers of the core of Chinese culture, encompassing literary, ideological, scientific, and artistic works. These include not only ancient texts but also modern works, spanning contributions from both the Han nationality and other ethnic minorities [9,12].

In the 21st century—an era of global exchange and integration—it is crucial to preserve the individuality of national culture while learning from the advanced cultures of other nations. To achieve this, we must prioritize the promotion of the Chinese language and spread the rich legacy of Chinese classics to the world. Translation of Chinese classics plays a pivotal role in this cultural exchange, facilitating the dissemination of traditional Chinese culture and enabling global audiences to understand China’s heritage [17].

The translation of Chinese classics also contributes to the development of the translation industry. Currently, challenges such as a shortage of skilled translators and insufficient expertise hinder the global dissemination of Chinese classics. Recognizing this, the state has strongly supported the translation and dissemination of Chinese classics, aiming to revive the field, attract talented professionals, and promote the growth of the translation industry. This support can drive the vigorous development of translation as a profession, ensuring the spread of Chinese culture on an international scale [16].

Chinese classics are invaluable treasures that reflect China’s long history and traditional culture. Against the backdrop of initiatives like the “One Belt and One Road,” translating Chinese classics has become an essential aspect of the “going out” strategy for Chinese culture. Efforts must be made to translate more Chinese classics into other languages, spreading traditional Chinese culture worldwide and fostering global understanding of China’s cultural heritage.

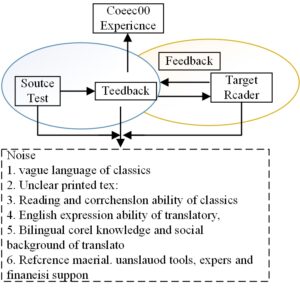

Based on the main elements of the dissemination mode and translation process, and considering the unique characteristics of the “Book of Changes,” such as its extensive use of culture-loaded words and vague language, a specific translation process is proposed.

As shown in Figure 1, the translator must first decipher the text by thoroughly understanding the author’s cultural background, intent, and philosophical significance. This understanding is then used to translate the text for the target audience. The audience subsequently decodes the translation and provides feedback to the translator. However, during this process, internal and external noise can impact the readers’ comprehension of the original text. From this model of the translation process, it becomes evident that the translator holds a central role in classical translation. Two key factors that influence translation quality are the ability to avoid noise and the identification of shared experiential areas. Additionally, feedback from the target audience is instrumental in improving the quality of the translation.

In this mode, the influence of noise is significant and originates from various sources:

**Noise from the Original Text**: Classical texts often contain linguistic fuzziness and ambiguous terms. For example, in the “Book of Changes,” the term “Tao” may convey different meanings depending on the context—sometimes referring to the origin of all things, other times to laws or the truths of human behavior. Such linguistic vagueness makes the text challenging to interpret. Furthermore, improper preservation of some classical documents has resulted in incoherent or illegible text, making it difficult for translators to fully comprehend the original work [11].

**Noise from the Translation Process**: The translator’s ability to read and interpret Chinese classics, their understanding of foreign history and culture, and their proficiency in foreign language writing directly affect translation quality. Insufficient expertise in any of these areas can introduce errors and inconsistencies.

**Noise from the Social Environment**: The translator’s social environment significantly influences the translation process. Factors such as access to sufficient information, advanced translation tools, financial support, and a conducive social setting play a vital role. Similarly, the readers’ social environment determines their ability to access relevant cultural background information, which is crucial for fully understanding and appreciating the translation [5].

During the translation process, it is essential to create intersections between the author’s and translator’s understanding of the original text and the translator’s and target readers’ interpretation of the translated text. The greater the overlap between these common areas of understanding, the easier it will be for target readers to experience the original text in a manner similar to its original audience.

From a linguistic perspective, translators should flexibly employ their bilingual reading and writing skills to bridge cultural and linguistic gaps. This approach ensures a more accurate and culturally sensitive translation, allowing target readers to better appreciate and engage with the text.

The German version of the “Book of Changes,” translated by German missionary Wilhelm and Mr. Lao Nauruan, is recognized as an authoritative translation. It has been translated into multiple languages and is widely circulated in the Western world.

In the preface to the “Book of Changes,” Wilhelm explained the collaborative translation process with Lao, which involved a flexible co-translation approach. Lao interpreted the hexagrams of the “Book of Changes” in Chinese, while Wilhelm translated them into German. Initially, Wilhelm drafted the German version without directly referencing the original Chinese text. This draft was then re-translated into Chinese and reviewed collaboratively with Lao to refine and perfect the German translation.

The first stage of the translation process typically involved two individuals: one interpreting the source language and the other generating the target language text. The mastery of “Book of Changes” and Chinese culture by Lao provided the foundation for this process, while Wilhelm’s linguistic expertise made his contribution indispensable. Their complementary strengths were key to the success of this collaborative effort.

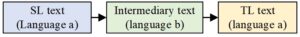

The second stage of the process involved “reverse translation,” where the target language text was retranslated into the source language to test the accuracy and completeness of the translation (see Figure 2). This process not only identified errors but also served as a bridge between translation and creation, fostering a productive interplay between languages and cultures.

Wilhelm’s German translation of the “Book of Changes,” published in 1924, caused a sensation in Western academic circles and was widely regarded as an authoritative work. Subsequently, Wilhelm’s student Baines translated the German version into English. After Wilhelm’s death, his son Wei Deming assisted Baines in reconciling the English translation with the original Chinese text, revising the preface, and finalizing what became the widely circulated “Wei-Baines” translation [10].

Baines’ translation did not begin directly with the classical Chinese version of the “Book of Changes” but was based on Wilhelm’s German translation. This indirect process, known as “relay translation,” involves translating a text from an intermediary language rather than directly from the source language (see Figure 3). Relay translation is common in cases where the source text is written in a less widely spoken language, and translators rely on existing translations in major languages like English to create target-language versions.

Relay translation has been widely used in the history of translation, particularly when translating texts from languages with fewer speakers into widely spoken languages. For example, early translations of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales and Marxist classics into Chinese were based on English and Russian versions. Translators often make choices based on the socio-cultural context, target audience expectations, and linguistic conventions of the time.

For instance, Baines modified the title of Wilhelm’s translation, changing “Ging” to “Ching” to align with the Wade-Giles romanization system, making it more consistent with English pronunciation. However, the term “I” was retained to convey spiritual connotations, aligning with the Western perception of the “Book of Changes” as a tool for self-salvation. This English version was highly praised by the renowned Swiss psychologist Carl Jung and became the “standard version” for Western scholars of the “Book of Changes,” eventually being translated into many languages and widely disseminated.

Pu Ledo adopted the “Wei-Baines” translation model but departed from its academic style to create a more accessible version of the “Book of Changes,” focusing on practical divination. The translation process transitioned from interlingual to intralingual translation, emphasizing readability and practicality (see Figure 4).

Pu’s translation draws heavily on the “Wei-Baines” model. For example, Pu retained Wilhelm’s translation of the hexagram “Qian” as “Ch’ien the Creative Principle,” highlighting its programmatic significance in the “Book of Changes.” However, Pu was not afraid to innovate. For instance, he translated a hexagram as “Sexual Intercourse,” a direct and bold choice that diverged significantly from earlier versions.

Compared to the “Wei-Baines” translation, Pu’s version prioritizes the practicality of divination in the “Book of Changes,” making it easier to understand and more engaging for readers [1]. This approach reflects the evolving expectations of readers and the translator’s willingness to adapt and innovate, further enriching the reception of the “Book of Changes” in diverse cultural contexts.

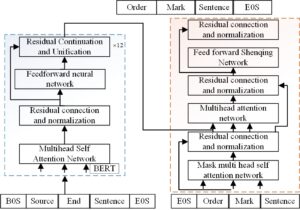

The Transformer model is a typical encoder-decoder structured network. The BERT pre-trained language model utilizes the encoder part of the Transformer, while GPT2 employs the decoder part of the Transformer. The characteristics and differences between BERT and GPT2 are summarized in Table 1.

| Description | BERT | GPT-2 |

| Parameter Quantity | 3 Billion | 15 Billion |

| Main Structure | Transformer – Encoder | Transformer – Decoder (without context attention) |

| Pre-training Task | Masked LM and Next Sentence Prediction | One-way language model |

| Input Vector | Token embedding, Position embedding | Token embedding, Position embedding, Segment embedding |

As a bidirectional self-encoding language model, BERT is well-suited as an encoder for feature extraction from text. On the other hand, GPT2, as an autoregressive language model based on the decoder part of the Transformer, excels in text generation. In the task of translating classical novels, two primary challenges arise: the lack of professional datasets and the long sequence lengths of the texts. This study introduces pre-training techniques by integrating BERT and GPT2 with encoder-decoder structures. This approach aims to jump-start the classical translation model, reducing its dependence on large-scale training data and improving its capability to handle longer sequences.

Three different fusion methods were explored in this study for classical novel translation tasks using parallel corpora of Chinese classics. Table 2 summarizes these fusion methods alongside the baseline models.

| Model | Encoder | Decoder |

| BERT2TD | BERT | Transformer Decoder |

| BERT2BERT | BERT | BERT |

| BERT2GPT2 | BERT | GPT-2 |

Figure 5 illustrates the structure of the BERT2TD model. In this approach, BERT serves as the encoder to generate source-side sentence encoding representations. The decoder follows the same 6-layer structure as the Transformer. All parameters of the decoder are initialized, and the source representation, weighted by the attention score, is passed through each layer to produce the output.

The structure of the BERT2GPT2 model is shown in Figure 6. Since GPT2 is an autoregressive language model optimized for decoding, its internal attention mechanism only considers information between previous time steps. To integrate GPT2 into the translation process, a multi-head attention mechanism is added at each layer for interaction with the encoder’s output. Additionally, GPT2’s pre-trained vocabulary uses the “|end of text|” token as the starting word for text generation. For the classical translation task, “[BOS]” (Beginning of Sentence) and “[EOS]” (End of Sentence) tokens are added to its vocabulary to define the start and end of sentences in the decoding process.

Through continuous experimentation, the optimal training hyperparameters were determined to achieve higher training efficiency and better performance. The learning rate strategy employed was a warmup hot-start approach with 4000 warmup steps. The maximum length of CNNs sentences was set to 70, and the batch size was set to 8. A grid search method was used to optimize hyperparameters, validated using a validation dataset, and the best model was selected [7].

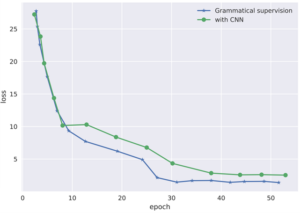

During training, the loss value of the validation set at each checkpoint was monitored in real-time, recorded, and plotted. This approach also mitigates overfitting. If the loss on consecutive validation sets either stagnates or increases, the training is stopped to prevent overfitting. Table 3 shows the loss statistics for the training process of the grammar-supervised sacred text translation model and the CNNs grammar-supervised sacred text translation model, with the corresponding loss curves depicted in Figure 7.

As shown in Table 3, the loss values of both models decreased continuously with an increase in training epochs. Initially, the loss decreased rapidly before reaching a plateau, where the reduction slowed but remained consistent, indicating ongoing model learning and improvement. The final loss value of the CNNs grammar-supervised model was lower than that of the grammar-supervised model, demonstrating its effectiveness.

| Epoch 0 | Epoch 3 | Epoch 12 | Epoch 24 | Epoch 36 | Epoch 48 | Epoch 60 | |

| Grammatical Supervision NMT | 26.05 | 14.79 | 7.84 | 5.65 | 2.43 | 2.43 | 2.43 |

| + CNNs Grammatical Supervision NMT | 26.90 | 14.85 | 7.85 | 6.50 | 5.38 | 3.46 | 2.35 |

From Figure 7, it can be seen that the training convergence time for the CNNs grammar-supervised model is longer than for the grammar-supervised model due to the larger number of parameters in the improved model (869 MB for the grammar-supervised model compared to 900.6 MB for the CNNs model). This requires more time for weight updates. Checkpointing during training ensures that progress is not lost due to interruptions, allowing the training to resume from the last save point.

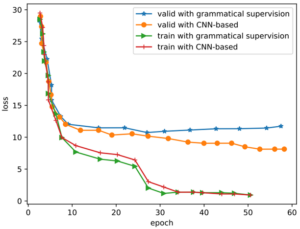

A validation process was conducted every few epochs to monitor the loss value, which offers two key benefits: 1. **Problem Identification**: Early detection of issues with the model or parameters (e.g., anomalies in the validation set) allows for timely intervention. 2. **Model Generalization Verification**: Validation loss provides insight into the model’s generalization ability, ensuring it performs well on unseen data. Table 4 shows the loss values for training and validation sets at various epochs, while Figure 8 illustrates the corresponding loss curves.

| Epoch 0 | Epoch 12 | Epoch 24 | Epoch 36 | Epoch 48 | Epoch 60 | |

| Train + Grammatical Supervision NMT | 26.05 | 7.84 | 5.65 | 2.43 | 2.43 | 2.43 |

| Train + CNNs Grammatical Supervision NMT | 26.90 | 7.85 | 6.50 | 5.38 | 3.46 | 2.35 |

| Valid + Grammatical Supervision NMT | 27.40 | 11.57 | 11.04 | 11.21 | 11.21 | 11.22 |

| Valid + CNNs Grammatical Supervision NMT | 26.10 | 11.14 | 10.55 | 9.69 | 9.13 | 8.48 |

From Figure 8, it is evident that the validation loss is generally higher than the training loss. The CNNs grammar-supervised model shows better performance on the validation set compared to the grammar-supervised model, reflecting its superior generalization ability. Convergence occurs around epochs 51-54 for the CNNs model and epochs 26-27 for the grammar-supervised model.

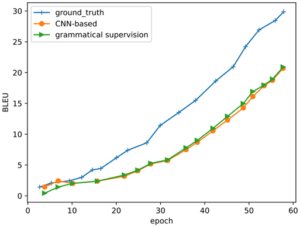

Finally, the BLEU scores of the models were evaluated, and the results are presented in Table 5 and Figure 9. The BLEU scores of the CNNs grammar-supervised model outperformed those of the grammar-supervised model, validating the effectiveness of adding sentence context topic attention modules.

| Epoch 3 | Epoch 12 | Epoch 24 | Epoch 36 | Epoch 48 | Epoch 60 | |

| Grammatical Supervision NMT BLEU | 0.30 | 1.96 | 4.87 | 10.92 | 21.02 | 36.10 |

| CNNs Grammatical Supervision NMT BLEU | 0.40 | 2.49 | 5.48 | 11.74 | 21.69 | 37.63 |

| Ground Truth Grammar Sequence – NMT BLEU | 0.60 | 3.46 | 10.90 | 22.43 | 36.98 | 52.73 |

Table 5 and Figure 9 indicate that BLEU scores increase with epochs. The CNNs grammar-supervised model achieved higher BLEU scores compared to the grammar-supervised model. The ground truth grammar sequence model performed the best, reaching a BLEU score of 52.73. This demonstrates that the CNNs-based improvements enhance the accuracy of grammar sequence prediction, resulting in better translation performance.

The *Book of Changes* embodies the sages’ profound understanding of nature and the universe, celebrated for its rich dialectical philosophy. However, its translation has long been challenging due to the intricate cultural nuances in its language and the deep philosophical heritage of *Yili*. While translations, from pioneers like James Legge and Wilhelm to modern efforts, have increased in diversity, none can claim absolute authority, as each faces limitations inherent to the complexities of the text. Similar challenges are encountered in translating other Chinese classics due to their unique linguistic and cultural features. This paper advocates for establishing cross-disciplinary and cross-cultural translation teams, enhancing Chinese classics-specific corpora, reshaping the value of indirect translation as a bridge across linguistic divides, and promoting translation criticism as a mechanism for continuous improvement. By implementing these strategies, the translation of Chinese classics can be significantly advanced, ensuring their accessibility to a global audience while preserving their rich cultural and philosophical essence.

1970-2025 CP (Manitoba, Canada) unless otherwise stated.